As a child, I once tripped and fell while carrying a long thin bamboo rod. When I hit the ground, the stick penetrated my right eye. I put my hand up to my face and it came back full of blood.

The hospital put a piratical patch on the injured eye. In a few days I took it off, and the sight was blurry, but still there. By great good luck I did not go blind, but merely lost some sight. My good eye (the left) is 20/40 and the injured one is 20/400, meaning I see up close what most people see from 400 feet away. With glasses I am essentially normal, so it is fine.

But to live in darkness: walking with a white cane, perhaps assisted by one of the famous “Seeing Eye Dogs”— if there was one available/affordable?

How do the blind cope? For them, neatness must be a necessity. They have to know exactly where everything goes, or how can they find it again? My room is a cheerful chaos of stacked books and binders; how would I function without sight?

In addition to the loss of independence, (not being able to drive, for one) blind folks are more likely to fall than sighted people, with risk of bone fractures and hospital costs.

And reading?

Louis Braille, cobbler, injured himself with an awl, a hand-held shoe repair tool. One eye went immediately blind, the other got infected and became blind too.

But Louis Braille worked a common-sense miracle. Using the same leather punch that had taken his sight, he made a series of indentations on a page, then flipped it over. Now he had a series of raised bumps in various configuration, each set of which meant a letter, like “a” or “b”—once he memorized their meaning, he could run his fingers across them, and know what they meant— reading for the blind.

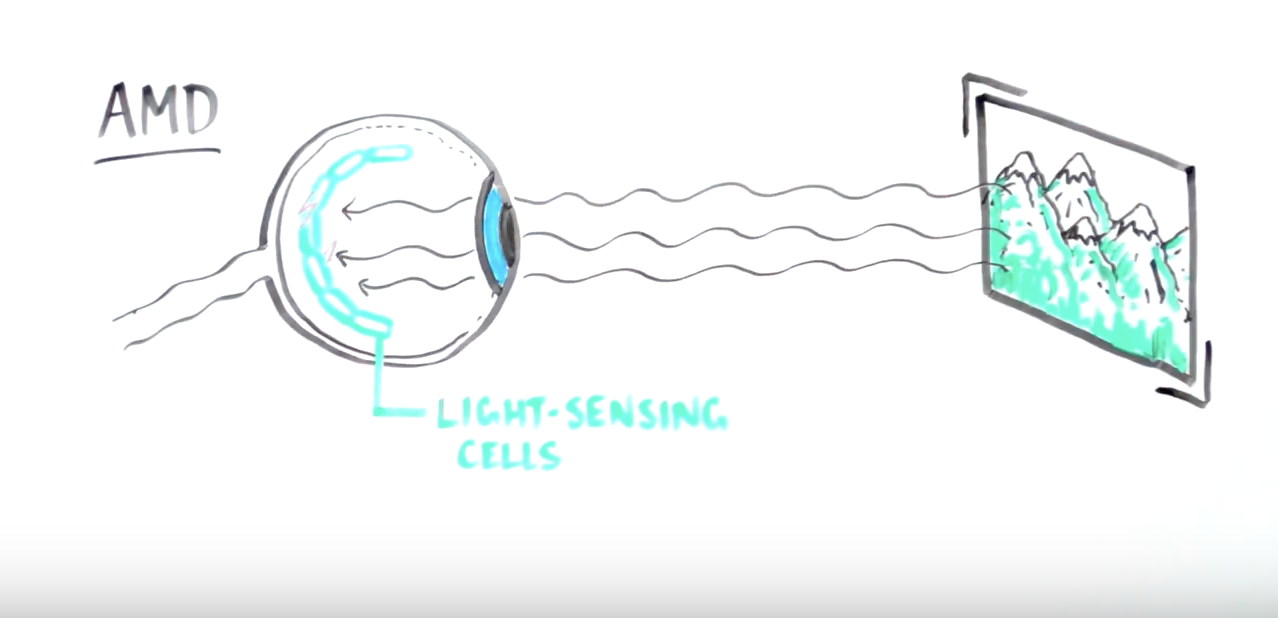

Earlier I wrote about age-related macular degeneration, a common form of blindness which affects the old.

But if it is terrible to go blind at 70 or 80—what would it be like for a teenager, to lose sight with their whole life still ahead?

Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) steals vision from roughly 1.5 million people world-wide: teenagers.

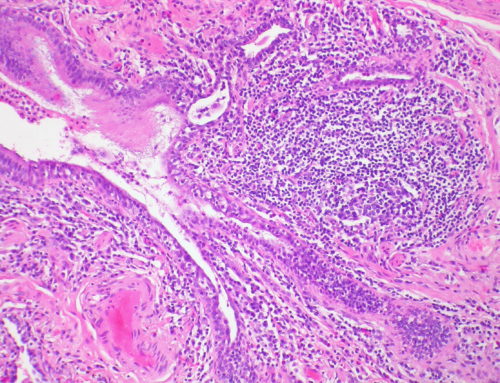

The disease does its damage by destroying light-sensing cells (photo-receptors) at the back of the eye, inside the retina. Healthy receptors turn light into electrical impulses, which the brain translates into pictures: vision. When RP strikes, the receptors die: becoming fewer and fewer, and the darkness closes in.

At the University of California at Irvine, Dr. Henry Klassen, M.D., Ph.D., is challenging RP.

How does it work?

Funded by the California stem cell program, Dr. Klassen has developed a gel with stem cells in it, at the stage called progenitors. This “inbetween” stage allows the cells to change inside the eye, perhaps becoming the missing cells, like young soldiers replacing old warriors, fallen on the field.

The whole procedure is just one injection, into the (numbed) worst-seeing eye.

I interviewed Dr. Henry Klassen, asking him how he became an eye scientist—he said what clinched it for him was…a pair of sunglasses?

Klassen’s Dad was a biology teacher, who often took his young son to work.

“I liked it there, and just absorbed information almost by osmosis. By the time I left the 6th grade I had a high school level understanding of biology. But I also had headaches, and trouble with bright lights… a visit to an opthmalogist left me with a prescription for sunglasses, which I thought very cool—and an interest in the science of the eye.”

How is the research going? I wanted to know about the patients themselves.

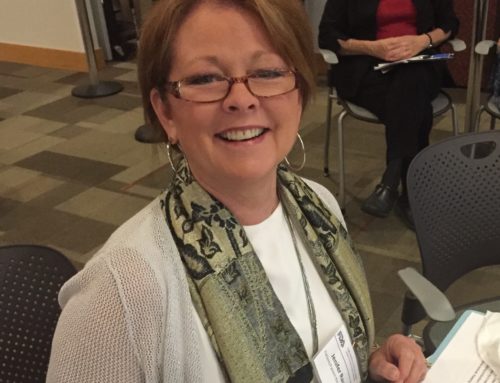

Kristin Macdonald had intended to become a movie actress. She was beautiful (that has not changed), had an agent and was doing the work to make it happen. But she kept tripping and falling, once on the very staircase where the Academy Awards are presented. She broke her arm, twice. Her night sight went; colors faded. Her vision became like seeing through a slowly closing straw…

“Retinitis pigmentosa,” said the doctor. Kristin started using a white cane. She remembered the first time she heard someone say, “Look out, here comes a blind person!”, and realizing they were talking about her…

But on June 20th, 2016, she was the first person in North America to have progenitor cells put in her eye. She had joined Dr. Klassen’s clinical trial.

It was only a safety trial; the amount of transplanted material allowed by the FDA for this early effort was small: no benefits expected. However…

“More light!”, she said, describing the results. Even the awareness of light was an improvement, allowing her to recognize obstacles in her path.

Today she is an Ambassador for Americans for Cures Foundation, driving the fight in ways only an advocate can, spreading the word, raising awareness. As she puts it: “My eyesight is bad, but my vision is perfect!”

Ms. MacDonald used her entertainment skills to establish and host her own radio show: the inspiring “SECOND VISION”. Check it out!

So how is the research coming, from the scientific point of view?

Klassen: “Over the past year, significant progress has been made in advancing our therapy…Eight patients in our first cohort and one patient in our second have been injected at two different dose levels: 0.5 million and 1.0 million cells…Our safety data (was) reviewed …no safety concerns.”

The stem cell product jCell) is so promising that the Food and Drug Administration has given it a boost: a way to possibly accelerate its progress through the often agonizingly long clinical trials.

The help is a special label, a designation, called “Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT)”, which came about through President Obama’s 21st Century Cures Act, a bi-partisan effort supported by Republicans and Democrats alike.

There may be unexpected benefits from the research. As Dr. Klassen puts it:

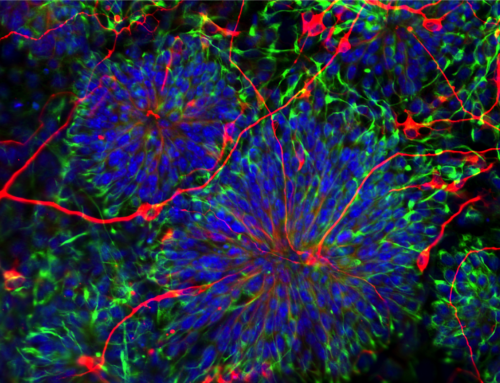

“The eye is an important proving ground for stem cell-based therapies, and (may) provide a stepping stone to many otherwise incurable diseases of the brain and spinal cord.”

This post originally appeared on HuffPost.

Don C. Reed is Vice President of Public Policy for Americans for Cures, and he is the author of the forthcoming book, CALIFORNIA CURES: How California is Challenging Chronic Disease: How We Are Beginning to Win—and Why We Must Do It Again! You can learn more here.