Did you see a movie called “THE BOY IN THE PLASTIC BUBBLE”, starring John Travolta? In the film, the hero has a disease called Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), which means his immune system does not work. Germs that you and I would not even know about (because our immune system would fight them off) could be fatal. To survive, he must live in sterile housing: the plastic bubble.

The movie was based on the true story of a boy named David Vetter.

In the Travolta movie, the boy in the bubble grows up, falls in love, and decides to leave his plastic refuge. His movie doctor tells him he may have built up some immunities; he steps out into the world, and rides off on a horse, behind his girl.

The real-life story did not have such a happy ending.

David Vetter’s family fought for him with tenacity, intelligence, and love. They managed to get him tremendous amounts of treatment, including help from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) which built him a space-suit device to wear, so he could go for a walk outside. It was cumbersome, and he only used it seven times.

The bubble had been set up as a temporary device. The family had lost another child to SCID, and this time they hoped science might provide them a cure, if given time. But when it did not arrive, the boy stayed there, for his own survival.

When his doctor, William T. Shearer, introduced himself, David Vetter put his hand up to the plastic wall—and on the other side, Dr. Shearer put his hand up to meet it.

At the age of 12, a transplant procedure was tried. David’s sister Katherine volunteered to give cells to him in a bone marrow transplant, just as she had done for his brother, years ago. At first, it seemed to be working. But hidden in the young woman’s body was traces of a dormant virus, Epstein-Barr, undetectable in the screening. It triggered a cancer, which overwhelmed the boy’s body.

The young man said to his doctor, “Here we have all of these tubes and all of these tests, and nothing’s working. I’m getting tired. Why don’t we pull all of these tubes out and let me go home?”

When David could no longer be effectively treated in the bubble, he was taken out: February 7th, 1984. His mother kissed him for the first time. But the lymphoma had spread throughout his body. His health deteriorated.

Importantly, David knew every step of the way what was going on, to the limits of his understanding. When he was four, he took a syringe and poked a hole in the bubble. Germs were explained to him, and from that point on the very bright child was kept fully informed.

His last conscious act was to wink at the doctor who had tried so hard to help him.

Then he passed away.

And this was the condition which threatened baby Evangelina Padilla Vaccaro.

“I knew something was wrong right away,” said her mother Alysia in a telephone interview:

“She had a gray color, did not move right, and she spit up a lot. … she had no immune system; her body had no way to fight back against germs; a cold could kill her. We made our house as sterile as we could. My husband Christian and I wore masks all the time. Evangelina never saw our mouths.”

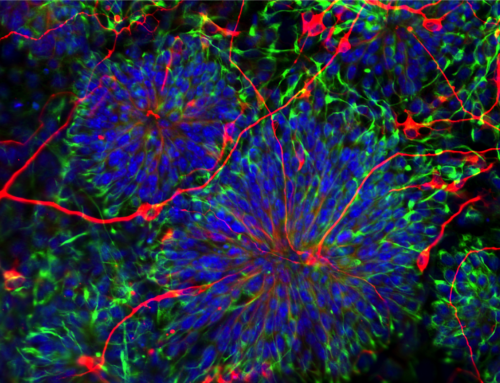

“And then I heard about stem cells and UCLA and Dr. Donald Kohn— and how it might be possible to rebuild Evangelina’s immune system.

“But stem cells? I had been raised a good Catholic girl, and had heard all kinds of bad things about stem cells. But when it is your child in danger, you will listen very carefully, and we did. This was about saving lives.

“There was just one opening left on the clinical trials… Dr. Kohn held it open for the two months it took our daughter to grow strong enough to endure the operation.

“Dr. Kohn was up front with us… never promising a cure. But my husband and I had read more than 30 studies on the National Institutes of Health website, trying to educate ourselves on what had been tried before on our daughter’s condition, and Dr. Kohn’s approach made sense.

“He would take out bone marrow from her hip. There was a mutation in her genes. He would fix the gene, put it into some stem cells, and put those back.

“I had had three miscarriages before the twins arrived… was I now to lose another of my children?”

And then, everything changed. Her mom and dad took Evangelina outside, and held her high in the air. She felt the sunlight for the first time. She opened her mouth, and laughed for sheer joy.

Evangelina had been given a gift from the people of California. Something small, and wonderful: a California cure.

I had the privilege of meeting Evangelina and her family at a California stem cell board meeting.

Evangelina was four years old by then, spunky, wearing a pink superhero T-shirt. She stepped up to the microphone, then jumped back, startled by the squeal of feedback. But she stuck to her task.

“Thank you,” she said, in a tiny voice.

Her Mom also spoke to the CIRM: “Thank you— for keeping my family together.”

When I talked to her later, she added, “If there is an effort to build Prop 71 part two, count me in!”

In the course of writing this article, I reached out to Dr. William T. Shearer, the doctor who had cared for David Vetter, wondering if he had any comments to make, having given so much of his life to SCID research and therapy. He responded:

“Dear Mr. Reed,

“I know Dr. Donald Kohn very well, and we are collaborators in the stem cell program. Dr. Kohn reconstitutes SCID children with a genetic insertion that corrects gene defect. Many children have benefited from his new form of SKID children reconstitution. I strongly support his research and clinical work with these special patients. Thank you for your note.

“Best wishes for you and your son in 2018.

“Sincerely, WTS”. (William T. Shearer, personal communication)

AND— he reached out to Carol Ann Demaret, Mrs. Vetter, David’s mother, who was willing to speak with me.

I was nervous before our talk. How would it feel for her, to have lost two children to a disease—for which there now existed a cure?

But I “recognized” her right away. She was an advocate, dedicated to the fight against a disease: Severe Combined Immunodeficiency: SCID. She has not quit. She talked about not letting the community down, forging ahead with research—continued help for future generations.

She explained some things I did not understand.

“The bubble was like a second womb,” she said, “We thought at first that David’s immune system was just late in developing, and if we just gave him a little time, it would activate.”

Sustained by strong faith and personal values, she has never given up.

“In the back of my mind, David’s loss is always there,” she said, “But when people ask me about the pain, I always tell them:

“God sent David to me; research gave us 12 years to spend with him.”

After David died, her biggest worry was that his sister Katherine might be a carrier, and might herself give birth to a child with SCID.

When Katherine was 23, married a year, and needing to know, Dr. Shearer called her into his office and told her: she was not a carrier.

Tomorrow, David Vetter’s mother will make a beautiful meal— for her two strong and healthy grandsons.

This post originally appeared on HuffPost.

Don C. Reed is Vice President of Public Policy for Americans for Cures, and he is the author of the forthcoming book, CALIFORNIA CURES: How California is Challenging Chronic Disease: How We Are Beginning to Win—and Why We Must Do It Again! You can learn more here.