Cancer patients hold onto hope the way some people hold onto the lap bars of roller coasters: As if their lives depend on it.

And then they get ready for the ups and downs.

Theresa Blanda and Nancy Davidson started their rides after they were diagnosed with rare and debilitating blood cancers that enlarge the spleen and can progress to complications that are fatal.

Both volunteered for a clinical trial with a drug developed by a small San Diego biotech company. Unlike the vast majority of trials, which end in disappointment, this one worked for them. The drug, fedratinib, made them better.

So much better that Blanda returned to her accounting work in the defense industry. She made plans to marry. She dreamed about traveling.

Davidson stopped worrying about whether she would live long enough to see her son and daughter graduate from high school and college.

Then, five years into the trial, eight patients developed what appeared to be a dangerous neurological disorder that causes brain swelling and confusion. One died. Was the drug responsible?

U.S. regulators put a safety hold on the medication, and rather than investigate further, the French pharmaceutical company that owned fedratinib walked away.

“I’ve never felt better and all of a sudden they’re gonna just take this drug away from me?” Davidson said. “Where do I go from here?”

Dr. Catriona Jamieson, an oncologist and researcher at UC San Diego, wondered the same thing. She was running the UCSD trial site with Davidson and Blanda in it. When they stopped using the drug, they got sicker.

As months went by, other physicians involved in clinical trials saw similar setbacks. One, in Michigan, reported that 11 of his patients, all of whom had responded well to fedratinib, died after they were taken off it.

Jamieson went to John Hood, a scientist and entrepreneur who had helped invent the drug. “We need to do something,” she said.

Hood had moved on to another San Diego biotech and wasn’t involved with the trials. But he still believed in the drug. “It was doing amazing things,” he said.

He jumped back in, eventually quitting his job to form a new company and putting up $250,000 of his own money to seed it. Could his team get the license for the drug back? Could they convince regulators that it was safe?

Could they do all that fast enough to keep Blanda and Davidson — and the other patients who depended on fedratinib — alive?

A gene called JAK2

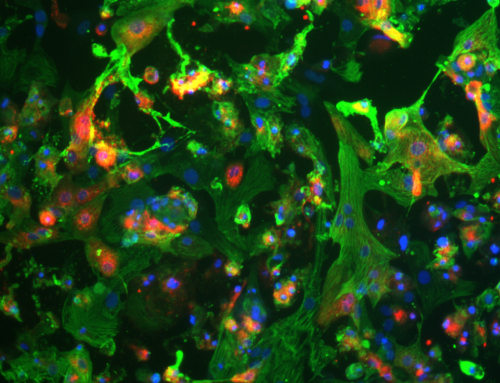

The two women, both Orange County residents, had blood cancers that belong to a group of progressive diseases arising in bone marrow and known collectively as myeloproliferative neoplasms. Often caused by a mutation in a gene called JAK2, they trigger excessive production of blood cells or platelets.

On the milder end of the spectrum, cancer causes the blood to thicken so it doesn’t flow easily, a problem treated with phlebotomy or medication. But it can also lead to myelofibrosis, where bone marrow is replaced by scar tissue, crowding out normal cells.

Those cells migrate to the spleen, causing it to enlarge and press against the stomach and other organs, which makes it difficult to eat or lie down. That can set off a dangerous cascade of reactions in the liver and elsewhere.

People at any age can get these diseases, but they hit most patients after they turn 60. There is no known cure. Although the cancer progresses slowly — some patients experience no symptoms for long periods of time — when it reaches an advanced stage, the projected life span is less than three years.

The importance of the JAK2 mutation was only discovered in 2005. The next year, Jamieson and colleagues showed it was active in blood stem cells in these diseases. This caught the attention of Hood and others at TargeGen, a San Diego biotech company founded in 2001. They began working on a drug to inhibit the mutation, with Hood, the director of research, spearheading the effort.

Hood, 53, grew up on a ranch in Texas, “in the middle of nowhere,” outside the town of Gladewater in the northeastern part of the state. There, with numerous animals to care for, Hood said he became aware of the cycle of life, and recognized that science could improve lives and stave off disease.

After earning a bachelor of science in biochemistry and a doctorate in medical physiology from Texas A&M University, he came to San Diego to do postdoctoral work at Scripps Research with David Cheresh, an immunologist who is now at UC San Diego. The technology at TargeGen was spun out of Cheresh’s lab.

San Diego’s biotech community is close-knit. Everybody knows everybody else, and many of them share the motivation Hood expressed once in a company newsletter: “There’s nothing more rewarding than knowing that the endpoint of your work is going to save lives.”

The endpoint of the work on JAK2 was fedratinib. Hood said this molecule met all the criteria of a useful drug: It was active against the target, wasn’t toxic to normal cells and could be taken by mouth.

Jamieson, at UCSD, studied the compound and also concluded it could be effective. In 2008, working with Hood and others, she designed a clinical trial and began accepting patients.

Blanda was the last one admitted that year in the initial study group. She was 57 and had stopped working as an accountant to be a full-time patient. She bruised easily. Her bones ached. She was tired all the time. Her spleen was enlarged. Myelofibrosis is measured on a scale from 0 to 4. She was a 3.

Fedratinib turned all that around. “It went,” Hood said, “from the worst of the worst to very much a phoenix being reborn.” Blanda’s new myelofibrosis rating: 0.

Davidson had a similar reaction. She was admitted to the trial in early 2013, when she was 46, as the testing neared completion. She suspects she was initially in the placebo group, because nothing was happening — nothing good, anyway. Her bones still hurt. Her spleen was still growing.

At Jamieson’s urging, she stayed in the trial and became part of a phase in which all the patients got the drug. She improved, too.

By then, TargeGen had been acquired by Sanofi, a French pharmaceutical company, for $75 million in upfront money and a total of up to $635 million if the drug met certain milestones. It seemed headed in that direction. Among the nearly 900 patients in 18 trials, the positive response rate was 50 to 60 percent, almost double the results seen in trials for a competing drug. It had fewer side effects, too.

Only about 5 to 10 percent of drugs that enter clinical testing make it to the finish line. Some of those are only modestly effective, or “me too” copycats. To have one like fedratinib, highly effective against a cancer that doesn’t often respond to other therapies, is the rarest of the rare — almost a poster child for pharmaceutical innovation.

Then, in late 2013, alarm bells went off.

Pulling the plug

A patient in France who had been on fedratinib for a few weeks developed Wernicke’s encephalopathy, a neurological disorder caused by a deficiency in vitamin B-1 and marked by brain swelling and confusion. Sanofi looked at the medical records of the other patients and identified seven more with symptoms suggestive of Wernicke’s.

The company alerted the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which put a hold on the trials pending further investigation. Just one business day later, Sanofi pulled the plug on the drug.

“We are deeply disappointed to have to discontinue development of fedratinib, especially given the needs of this difficult-to-treat patient population and the earlier promise shown for this therapy,” Sanofi’s head of development, Dr. Tal Zaks, said in a press release. “But patient safety is our top priority and drove this decision.”

Some suspected financial motivations as well. Sanofi would have had to pay investors hundreds of millions of dollars if the drug made it through regulatory approval. And a competing drug, called Jakafi, had beaten fedratinib to the market. It was approved in 2011.

But the reason didn’t matter much to patients like Blanda and Davidson. What mattered to them was that a lifeline was no longer available. They were switched to other drugs, but those didn’t work as well.

Blanda’s spleen enlarged. Her liver acted up. Her knees enlarged, from migrating bone marrow. She needed platelet transfusions and wound up in the hospital.

“It’s been tough, let me tell you,” she said to a group of cancer doctors and researchers gathered at a symposium in San Diego in February 2015.

She looked gaunt. But she was hopeful about a new experimental drug she was taking. She talked about gaining weight, smiled at the prospect of getting married to a high school flame with whom she’d reconnected.

Blanda was fighting for her life — Jamieson called her the personification of “ganbatte,” a Japanese word that means “never give up” — and she thanked the physicians and scientists for helping her.

“I feel blessed and lucky that there are people like you who are doing this kind of thing,” Blanda told them. “It needs to be done. It’ll always need to be done.”

Davidson felt like she was in a holding pattern. The other drugs stopped her enlarged spleen from growing, but didn’t shrink it the way fedratinib did. Not only was the bigger spleen uncomfortable, hindering her breathing and sleep, it was vulnerable to injury. She stopped sailing, a lifelong passion, because it was too risky. Wherever she went, she shielded her spleen.

Jamieson and other doctors involved in the trials became frustrated and angry as they watched their patients get sick again. It made no sense to them that the drug had been pulled without further investigation.

Born in the Chilean coal-mining town of Lota, on the central coast, Jamieson got interested in medicine as a child. “My dad was a coal mining engineer, and it was clear there that health care wasn’ta right but a privilege,” she said. “There were a lot of very poor people who didn’t have access to health care.”

Jamieson earned her medical degree from the University of British Columbia and did her residency and a research fellowship in bone marrow transplantation and hematology at Stanford University. She worked in the lab of Irving Weissman, a noted researcher of stem cells and blood development.

She arrived at UCSD in 2005 and quickly became known as a leader in San Diego’s life science community. As a practicing oncologist who specialized in blood cancers, she also treated many myeloproliferative neoplasm patients.

As she watched some of those patients plunged into faltering health after fedratinib was pulled, she asked Hood if he could do anything.

Hood had moved on to another San Diego biotech, Samumed, but he still had a personal interest in fedratinib. He’d helped invent it, helped set up the clinical trials. It was very much his baby.

He negotiated with the FDA and Sanofi for a “compassionate use” exemption for patients who had gotten better on the drug. He received the approval on a Friday in 2016, and was set to work out the logistics the following Monday.

That was too late for Blanda. She died that Sunday.

Hood felt there was only one choice for him now. Somebody had to get fedratinib back in play.

With his wife’s blessing, he quit his job to start a new company. He called it Impact Biomedicines.

‘Make them listen’

They needed money. Hood put in $250,000 and worked with venture capitalists on a plan that would satisfy initial investors in the drug. The deal was contingent on lining up an additional $5 million — and doing it in 120 days.

Hood convinced Medicxi Ventures, a UK-based investment group, to participate. In October 2017, Medicxi put in $22.5 million. Later that month, Oberland Capital put in $90 million.

While the fundraising was going on, the team worked on another vital part of the puzzle: getting the FDA to lift its hold. Hood, Jamieson and another team member, Curtis Scribner, pored over the records of the eight patients who appeared to have come down with Wernicke’s while taking fedratinib. They brought in neurologists and other experts for consultations.

They concluded that most of the cases weren’t Wernicke’s, and that fedratinib wasn’t at fault. Those with Wernicke’s had a vitamin B-1 deficiency that was preventable and treatable. The others had underlying medical conditions. Even if all the incidents had been Wernicke’s, the number of them was still below what would be expected in the general population.

Hood’s team made its case to the regulators and got turned down. The drug remained on hold. Hood was disappointed, but not surprised.

“The FDA was understandably a little(reluctant) to believe that this little two-man company, with Catriona Jamieson from UCSD as the consulting physician, could really see something that Sanofi didn’t,” he said. “We had to keep going back to them, make them listen.”

Scribner, using his knowledge of the regulatory system, sent a letter appealing the rejection to Dr. Ann Farrell, the FDA’s director for hematology and oncology. She called and left a voicemail: She was reading the file. The next morning, she called again.

“I have reviewed all the data,” Scribner remembered her saying. “I understand your position. You are no longer on clinical hold.”

Hood said that moment was one of the happiest of his life. He felt like a 5-year-old on Christmas morning.

But his joy was tempered by what had been lost along the way. He thought of Theresa Blanda.

“Her dying when we were so close was the precipitating event that led me to quit my job and dedicate myself to getting rights to the drug from Sanofi, starting Impact and getting the hold lifted,” he said.

Blanda’s funeral drew lots of her defense industry co-workers. “She was very popular there,” said Jamieson, who also attended. “She was the one who would always troubleshoot, always help other people.”

That same attitude fueled Blanda’s involvement in clinical trials, Jamieson said.

“Her idea was that if people are going to work hard to get her better, she’s going to fight just as hard and, if anything, harder, so that other people also have an opportunity.”

People like Nancy Davidson.

Able to breathe

She feels better than she has in decades.

Through a compassionate-use waiver, Davidson went back on fedratinib in February. Her spleen has dropped in size almost 50 percent. “It hasn’t been that way since before I had kids,” she said.

Her son, Ryan, is 26 and her daughter, Bailey, is 24. For the longest time Davidson dared not dream of watching them reach certain milestones.

“I was always waiting for the other shoe to drop,” she said. “First, I wanted to see them get into kindergarten, and then to get them to high school. And by the time I got on fedratinib, it was, ‘Nancy, you’re going to see your kids graduate from college, so everything’s OK.’”

She’s making other adjustments. “I’m not going to sleep and thinking, Oh, I feel awful,” she said. “Or thinking I drank too much, after I’ve only had half a glass of water. Or that I ate too much, after just half a hamburger.”

But she’s been on the cancer roller coaster for decades, ever since her diagnosis at 19, so she’s learned not to get her hopes up too high. “Part of me is excited to get back on a drug I know worked in the past,” she said. “But just because it worked the first time doesn’t mean it will keep working now. And the disease is further along now.”

Wait and see, she said. But she’s optimistic. “I feel like I’m getting the physical stuff under control,” she said. “I’m able to breathe, both literally and figuratively.”

Hood is breathing easier, too, after three years of whirlwind activity to get the drug available again for patients. First it was raising the money and obtaining FDA clearance. Then it was a stream of top pharmaceutical suitors knocking on his door. They wanted to buy Impact Biomedicine and fedratinib.

In January of 2018, Celgene won the bidding. The price: $1.1 billion upfront, with billions more possible, depending on the ongoing success of the drug. It cleared its final FDA hurdle in August, and Celgene sells it now under the brand name Inrebic.

Early last year, Hood and his wife, Sally, bought a 6,300 square-foot home in Del Mar for $21.5 million, the biggest home sale in the county in a decade. Hood uses part of it for a home office while he ponders his next venture. He’s working on another company, this one focused on breast cancer.

He’s become a rock star in biotech circles, asked to share the boom-to-bust-to boom story of fedratinib. In his speeches, his presentations, his interviews, he tries to dissuade anyone from calling him a hero.

“This was the patients,” Hood said. “The patients made this happen.”

Journey of a cancer drug

2006: A San Diego company named TargeGen begins to research a drug for certain blood cancers called myeloproliferative neoplasms. The drug targets a mutation known to be involved in these diseases.

2006-2008: Dr. Catriona Jamieson, a UCSD physician/researcher who treats patients with these cancers, validates the drug’s potential. She helps design clinical studies to test the drug, which gets the generic name of fedratinib.

2010: TargeGen is purchased by French drug giant Sanofi, on the promise of fedratinib. TargeGen research director John Hood moves on to another company, confident the drug is on the right path.

2010-2013: Fedratinib continues to progress through clinical testing, and patients show strong response.

November 2013: Sanofi halts testing because of reports of eight patient illnesses, including one death. Drug is very close to being submitted for approval. Patients who had thrived on the drug seek alternatives.

2014-2016: Some patients who responded to the drug begin dying. Jamieson and other oncologists plead with Hood for help.

March 2016: Hood quits his job to form a company to rescue fedratinib, called Impact Biomedicines. Hood puts down $250,000 of his own money to get it off the ground, and keeps searching for more investors.

October 2017: Hood raises millions more, enough to complete the nearly-finished clinical trial process.

January 2018: U.S. pharma company Celgene buys Impact Biomedicines on the promise of fedratinib. Celgene pays $1 billion cash and up to a total of $7 billion including drug milestones.

Aug. 16, 2019: Fedratinib approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

— Bradley J. Fikes