One day in the eleventh grade, I did a thousand situps without stopping; I don’t know why. I just started doing them in PE class, going for a hundred at first, then continuing on and on. The person holding my ankles got bored and quit; somebody else tossed a cupful of water on the floor where my back kept touching. But I was on a mission and kept on and on, a skinny teenager doing situps…

I wore a patch of skin the size of a silver dollar off my tailbone area. It was raw and itched for a couple of days— and then healed without complication. That’s important.

But what if the skin could not heal?

Try this. Take your right index finger and run it roughly across your left forearm. Nothing happens, right? You see the skin ripple, but it springs back like before.

If you had a skin condition called Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB), that small touch could leave a blister, or expose raw flesh.

When you first meet John Hudson Dilgen, the “Boy with Butterfly Skin”, he appears to be wearing white sweats. He is smiling and talking, a regular kid, the athletic type who would be running around like crazy at the school playground, and be last to come in from recess.

It takes a moment to realize the “white sweats” are bandages over wounds.

The title “Butterfly skin” comes because EB skin is fragile as a butterfly’s wing.

In a healthy body, the layers of skin stick together by the body’s natural glue, collagen. In EB, the collagen gene does not work right, and the outer layer of skin can easily break away.

When John was born, he had no skin on his feet— from just the strain of childbirth. As he grew, more terrors developed.

“Bathtime”, said his mother, was “heartbreaking, with relentless fear and screaming…”

He loved potato chips, but just swallowing something rough can be deadly for a child with EB, doing damage to the inside of the throat.

And the parents? Imagine being afraid to hug your child, lest you damage them!

Today John Delgin is a teenager, but the disease is still with him. If he rubs his eyes, the damage may require him to spend several days in a completely dark room.

EB is rare, an “orphan disease”. This is good news/bad news: we want it rare, because no child should have to suffer like that—but a small number of patients also means fewer customers, less profit for the big corporations.

But there are practical reasons to support “orphan disease” research. Other conditions are similar: improvements for one may help another.

EB is rare, but skin disease is common, affecting 2% of the population. Wound healing in general affects millions. Finally, research on EB may accelerate cure for cancer. EB sufferers often die of a deadly cancer called squamous cell carcinoma. Studying the skin of an EB patient may determine the trigger-point of many kinds of cancer— exactly when and how it begins— potentially benefiting millions.

“… treating rare diseases is the first step toward achieving…(the) personalized medicine that the Obama Administration has highlighted as a priority.”—Julia Jenkins, Executive Director, Every Life Foundation for Rare Diseases— personal communication.

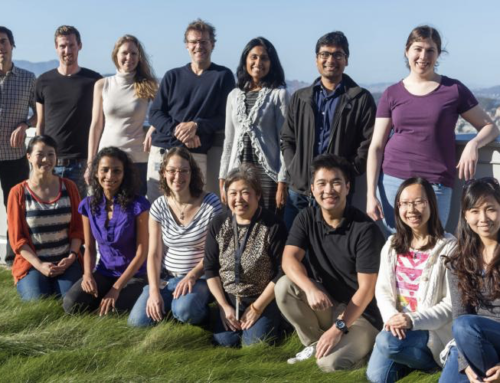

Stanford University is heavily invested in this effort, with a superb dermatology lab. More recently they have started a whole program to develop tissue and cell manufacturing technologies called the Center for Definitive and Curative Medicine(2)

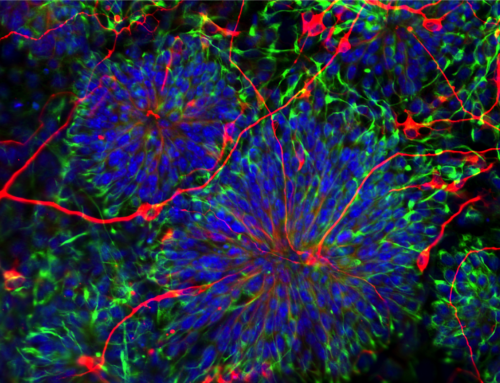

Here are Stanford scientists, working on the problem right now.

They are: Anthony Oro, Primary Investigator (PI) and a skin genetics and development expert, who is not only attempting to do the impossible with the invisible in medical research, but can even explain it in people-talk; and Marius Wernig, stem cell reprogramming authority, who once came to a formal science event wearing white tennis shoes with his tuxedo. The two are co-directing the project with a talented team including Project Manager and EB physician Jean Tang, Stanford Good Manufacturing Process Director David Digiusto, the head of the EB group and the University of Colorado, Dennis Roop, and the head of the EB effort at Columbia University, Angela Christiano. Together this EB iPS Consortium hopes to put their heads together to produce an iPS -derived product.

How will they try to defeat this presently incurable disease?

One weapon they may use is Induced Pluripotent Stem cells (iPS), the micro-manipulation of skin cells which won Shinya Yamanaka the Nobel prize.

And if they win? “There are over 200 genetic skin diseases that could in principle be treated with this approach. Similar therapeutic reprogramming studies are being developed for other tissues like heart, brain, pancreas, liver and cornea. The ‘road plowed with skin’ can make the manufacturing and regulatory tracks much easier for subsequent therapies.” – Anthony Oro, Stanford, personal communication.

Here is my layman’s interpretation of what they plan to do:

1. Take a tiny skin sample from the patient;

2. Using Professor Yamanaka’s iPS process, make personalized stem cells from the patient, “regressing” the cells back to an embryonic-like state;

3. Correct the defective genes;

4. Do quality control on the corrected iPS lines to remove those with genetic abnormalities;

5. Make new cells (with the corrected genes);

6. Make the healthy new skin and graft it onto the patient’s wounds.

Have they won? Not yet.

One attempt has failed; another is intended. Like a series of advancing waves, science moves forward, every effort benefiting from what went before.

Will the Oro/Wernig approach be the one that succeeds? We cannot know. But the fact that these talented individuals are fighting on gives me hope.

“Stanford…will soon move forward with an expanded patient study… We are hopefully years, not decades, away from meaningful therapies and potential cures.” —Jessica Schneer, Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Partnership Executive Director, personal communication.

Want to follow the research to fight “butterfly skin”? Click here:

P.S. To my delight, progress is being made to grow strong new skin for EB sufferers!

Dr. Anthony Oro’s work continues—as I understand it, small patches of skin will be removed from an EB patient, genetically altered (fixing the weakness) and then put back, where they will grow as sheets of normal healthy tissue.

Watch for grant number TRAN1-10416, called “Genetically Corrected, Induced Pluripotent Cell-Derived Epithelial Sheets for Definitive Treatment of Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa”.

I love those two words: “Definitive Treatment”….

AND—news just in from Italy, Dr. Michele De Luca and Reggio Emilia of the University of Modena have used another stem cell approach to regrow skin on an EB sufferer—congratulations!

My grandson Jason plays baseball, and does not worry about his skin; every kid deserves such fun and ease of mind. Bumped elbows and skinned knees should be a normal part of a child’s life, a minor inconvenience, nothing more— and epidermolysis bullosa should be remembered only because it is a hard word to pronounce.