In 1951, I was six years old and living in a hospital bed. I had asthma/bronchitis, which may not sound like much, nowadays. But every inhalation was a separate wheezing effort, and a choice: to struggle and breathe, or relax and die. There were injections of adrenaline which burned like liquid fire, and experimental drugs with long Latin names. With the passing of time, exercise stretched my ribcage and opened the bronchial tubes; but still it was many years before the condition loosed its claws from out my chest.

Lung disease…what a vile thing! The wheezing sound of your own breathing keeps you awake at night. And since every activity requires oxygen, if you cannot get enough, you just stop. Even walking can be too much; I remember stopping on the way to the store, bending over, hands on knees, straining for air.

And lung disease leaves scars…

Now, fast-forward sixty years. Enter Dr. Brigitte Gomperts, MD. Her studies focus on the repair and construction of the lung. Partially funded by California’s stem cell agency, Dr. Gomperts, Dan Wilkinson and others work at UCLA, in partnership with the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine.

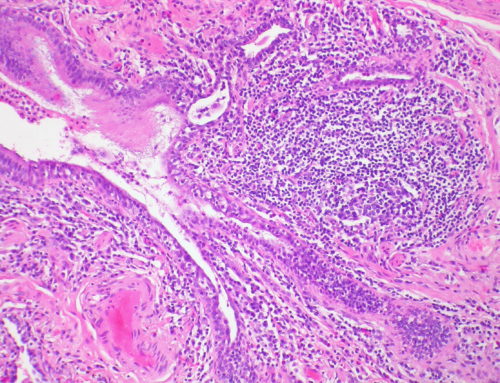

Remember those lung scars? There is a deadly lung disease called Idiopathic (incurable) Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), characterized by lung scars. When these grow too thick, the lungs become stiff. You cannot breathe, and the body shuts down.

“IPF is thought to affect more than 200,000 people in the USA …mortality is very high. About 2/3 of patients die within five years of diagnosis…IPF is on the rise and expected to double as the U.S. population continues to age…”

The only effective therapy? Transplantation. Lungs are taken from an organ donor, and put into the chest of someone who needs them.

But suitable lungs are hard to come by, and the transplant procedure is expensive, roughly half a million dollars. Never 100% safe, lung transplants may bring infections: or the body may reject the new lung.

One problem is the lack of a good disease “model”, a way to study the condition from beginning to end. If we can inject disease into a lab rat, we might find “markers” of the first signs of illness, and stop it early. But if we cannot find the beginning, it is hard to bring it to an end.

Also, animals may not have the same symptoms as we do. For instance, IPF lung scars on a mouse will go away after a while; those on humans never will.

But what if those diseased cells could be grown in a Petri dish…?

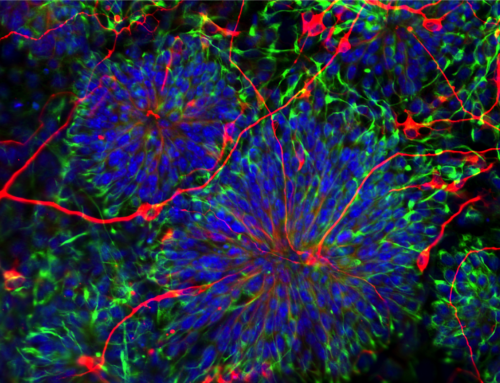

Using small chunks of skin from an IPF patient, Dr. Gomperts’ lab made cells, with scarring very similar to the disease. Now she can follow its progress: actually watch the scars develop—and with no patients suffering.

Her team took blood samples from 250 patients with IPF, and converted them into cell lines to study.

Could stem cells heal a damaged lung, converting scars into healthy tissue? That may be one way to bring relief.

Also, Dr. Gomperts is working with bioengineers to build an actual working lung, to transplant.

Want the “recipe”?

First, ingredients. Mix three different kinds of lung cells: epithelial (surface of the lung), fibroblasts (structural support) and endothelial cells (lining for the tiny veins, the capillaries) and apply to a biodegradable structure, to give it shape.

Wait for it to grow into alveoli, “the tiny breathing sacks of the lung”…

When those cells assemble— transplant as needed!

If successful, the replacement lung will be smaller than the original, and perhaps not as efficient. But it might keep an elderly patient alive while waiting for a donor lung. Or, it could save the life of a child. A premature baby may need a new lung; as might a child with underdeveloped lungs, or one who is lacking sufficient breathing cells.

Right now the new “lungs” are at the state of “organoids”, very small three-dimensional imitations of lungs. But this similarity may be close enough to make them good models of the disease, to be then testable in the search for cures.

Try this: the next time you need to take a breath (i.e. now)… consider what will happen if you cannot complete the process.

“To breathe or not to breathe; that is the question.” That may not be Shakespeare, but it is indeed the breath of life.

This post originally appeared on HuffPost.

Don C. Reed is Vice President of Public Policy for Americans for Cures, and he is the author of the forthcoming book, CALIFORNIA CURES: How California is Challenging Chronic Disease: How We Are Beginning to Win—and Why We Must Do It Again! You can learn more here.