If Dr. Tracy Grikscheit’s work prevails, one day the world may know something most of us never think about— how to improve defective intestines.

Why would we want to do such a thing?

To save a baby’s life.

First, consider the problem.

A premature infant may weigh 500 grams. Born too soon, their intestines may be susceptible to a condition called Short Bowel Syndrome (SBS).

At present, options for remediation are few, and unsatisfactory.

To save the child’s life, a surgeon like Dr. Grikscheit, (M.D., at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles) must perform a demanding operation. Like a length of rope, the intestines are lifted out of the body— both ends still attached— and the non-working bits are removed. The remainder is sewn back together, and replaced.

But what remains may not be enough. If the intestine does not have enough surface area to absorb nutrition, the child may need intravenous feeding, which can have complications of its own.

Or, the child may require a small bowel transplant: someone else’s intestines are put in, with all the problems of donor availability, and the body’s rejection of another person’s parts.

Even with a successful operation, in cases where much of the intestine has been destroyed, the child’s chances of survival are not high— the really small premature children who require resection of most of their intestine may not survive long enough to receive a transplant.

As Dr. Grikscheit said in her application for a grant from the California stem cell program:

“Small bowel transplants… have many problems, including poor graft survival, rejection, limited donor supply, surgical morbidity, and a lifelong (need for) immunosuppression.”

Instead— imagine the doctor saying: “We’re going to make a TESI for your child!”

Tessy? What’s that?

Making a usable Tissue Engineered Small Intestine (TESI) is one of the goals of Dr. Grikscheit’s professional life.

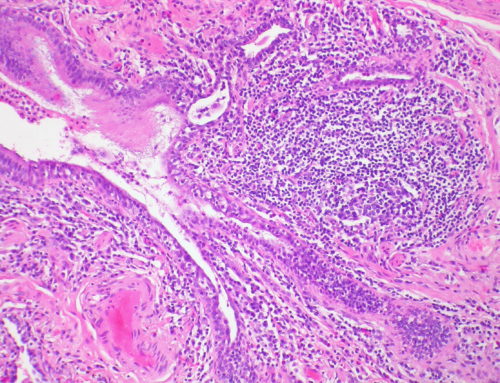

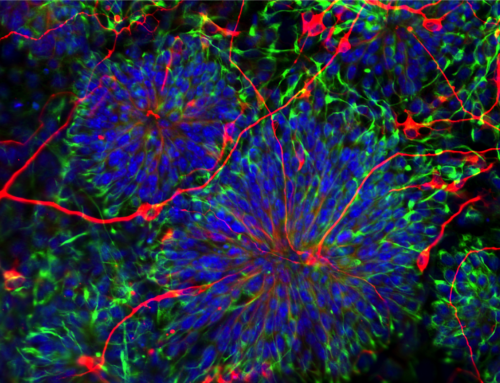

Basically, a tiny dissolvable scaffold is made. It is hoped that some of the baby’s own cells will be put on this scaffold, possibly encouraged by a growth factor. This living tissue would be placed inside the baby, and his/her life would go on, and become normal.

Is this possible?

Working on a grant from the California stem cell program, Dr. G. reports:

“We have shown that TESI forms when autologous cells (from the patient) are implanted on a polymer scaffold, and that TESI exactly (duplicates) native intestine… Importantly, animals recover from massive small bowel resection with TESI. Other regions of the gut (may also be made) via this approach.

“Our goal is to translate TESI … to an autologous human cell based therapy. Patients who needed emergency surgery for their intestine…could potentially be treated with TESI…Usable engineered intestines would be far less expensive, more durable, and require less maintenance than any current therapy.”

And a family goes home happy from the hospital…

As Dr. Grikscheit puts it, “We need to give these children a better future, measured not in months, but in decades like the rest of us.”

This post originally appeared on HuffPost.

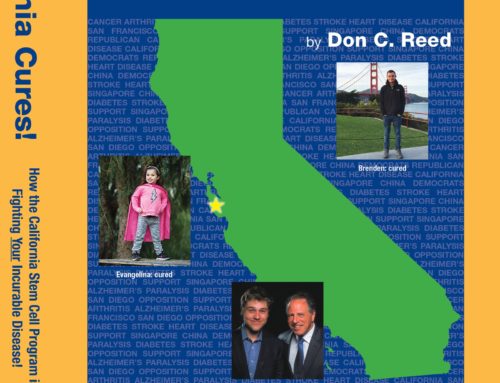

Don C. Reed is Vice President of Public Policy for Americans for Cures, and he is the author of the forthcoming book, CALIFORNIA CURES: How California is Challenging Chronic Disease: How We Are Beginning to Win—and Why We Must Do It Again! You can learn more here.