My recent bout with cancer resulted in a medical bill of $960,000. Think of that— almost a million bucks for the surgery, radiation, hormone injections, etc.— how could Gloria, life-partner of 48 years, and I possibly pay such an enormous bill?

We are senior citizens on a limited income. I have no savings, no stocks or bonds. In fact, about the only asset of value we possess is whatever equity is in our house.

So what should we do? Declare bankruptcy? Sell the house and be homeless? Or just borrow on the house as much as we could, make endless payments thereafter, and live low for the rest of our lives?

Fortunately, we have excellent insurance (Kaiser), which covered everything.

But not everyone is so lucky.

Too many suffer bankruptcies for medical causes.

First, did you know that before Senator Elizabeth Warren became a politician she was a Professor of law at Harvard, specializing in bankruptcy?

According to a major paper she co-authored, “Medical Bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: Results of a National Study”, the majority of bankruptcies happened because of medical difficulties. And it was getting progressively worse.

1981: “Only 8% (eight) of families filing for bankruptcy did so in the aftermath of a serious medical problem…

2001: “…illness or medical bills contributed to about half (emphasis added) of bankruptcies…”

2007: “62.1 % of all bankruptcies (in America) were medical…”

That study was cited by President Barack Obama in his 2009 State of the Union address.

What about Obamacare, the Affordable Care Agency (ACA) did that make a difference? It did, and a hugely beneficial one:

“Since (ACA’s) adoption, far fewer Americans have taken the extreme step of filing for personal bankruptcy.

“Filings have dropped about 50%, from 1,536,799 in 2010 to 770,846 in 2016.”

Unfortunately, Republicans are making a determined effort to end Obamacare.

Naturally, I am 100% opposed to their efforts.

But that is not what this article is about.

No matter where you stand on the issue of insurance, whether you support publicly funded, privately funded, or a mix of funding sources for insurance— we can all agree on one thing:

Chronic (incurable) illness costs too much.

What if, instead of arguing about who is going to pay for this mountain of medical debt— we could lower the mountain itself, reducing cost by eliminating diseases?

Cure research works.

Example: polio.

If Jonas Salk had not invented the polio vaccine, America would now be paying about $100 billion a year just to keep polio sufferers alive: not making them well, just keeping them inside iron lungs, 24 hours a day, waiting miserably for the end.

Thanks to cure research, polio is pretty much gone. It took many years, and a whole bunch of dollars.

But such benefit came from that research. We do not have to pay those incredibly massive bills, nor suffer the agony of living in iron lungs, nor watch our loved ones slowly die.

Cure research is how we can do that again, fighting chronic disease systematically.

And that is what California is doing.

We are fighting cancer, paralysis, blindness, arthritis, heart disease and more—to help people who would otherwise suffer physical and financial agonies, including the possibility of medical bankruptcy.

The path to cure is slow and hard.

But is it needed?

For a look at some of the expenses involved, visit the nation’s most trusted source of medical information: the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

As of 2012, about half of all American adults—117 million people—had one or more chronic health conditions. Eighty-six per cent of the nation’s $2.7 trillion annual health care expenditures are for people with chronic physical and mental health conditions.

Total annual cardiovascular diseases cost America $316 billion in 2012.

Cancer care cost $157 billion in 2010 dollars.

The cost of diabetes in 2012 was $245 billion.

Can cures come?

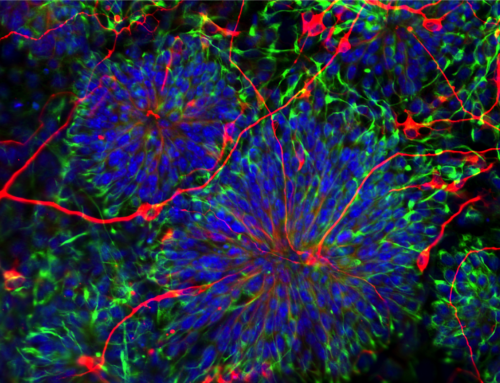

It is nearly Christmas as this is written. And the California stem cell program—CIRM, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine— is working hard as always: funding scientists whose research may ease suffering, save lives—and possibly prevent medical bankruptcies.

Most of the time, the decisions they make affect are not directly related to my family. That is right and proper; there are so many diseases and disabilities. For any to win, the entire field must advance.

But yesterday was different. Yesterday’s public meeting of the Independent Citizens’ Oversight Committee had an agenda item that affected me personally.

A scientist, Mark Tuszynski, had applied for a grant of $2 million to tackle spinal cord injury paralysis. I am the father of a paralyzed young man, Roman Reed.

The grant had been denied by the out-of-state review board, receiving a grade of 80, when the cutoff for funding was 85.

But the final decision was in the board’s hands. They are the voice of the people, and have the final say.

If the board approved the funding, Dr. Tuszynski of UCSD, would be challenging the condition which has afflicted my son since September 10th, 1994. Roman does not whine or complain. But I am his father, I see what paralysis costs him.

Naturally, I was at the meeting where that decision would be made. I had my speech ready, (three minutes for any member of the public) scribbled on the back of the meeting’s agenda.

First, Senator Art Torres (ret) raised the project as one perhaps deserving of re-consideration. I did not note who seconded his motion…Arlene DuLiege? I was a little nervous at the time, and had stopped taking notes.

Board members gave their opinion. One commented that the review board was experts and the board should not lightly go against them. Another pointed out the board represented the public, and had the right to disagree.

Public comment was taken (you can be sure I was first to the microphone!); Bob Klein spoke, and Arlene Chiu, the first Scientific Director of CIRM. The scientist doing the research, Mark Tuszynski, clarified some points.

And then the room was quiet; there was no more to say.

One by one the names were called, the votes were recorded. There were abstentions, four of them … but by my count, everybody else voted yes.

“Is that it? Did we win?” said the scientist. I told him yes, and punched him on the arm. I think it took him about an hour before he finally accepted that yes, he had won, $2 million of research money would be allocated to his battle against paralysis. There would be milestones, of course; if uncrossable obstacles occurred, the unspent money would be returned. But Dr. Tuszynski would have his chance.

One day, paralysis will be cured. A way will be found to bridge the injury, and restore connection to the brain.

Maybe it will happen while Roman and I are alive to cheer for it; maybe he will be among the first to walk. Or maybe not. Science comes at its own pace.

But when the day comes that people walk again, and paralysis becomes scarce as polio, we might remember yesterday:

December 14, 2017. When a giant step toward cure was taken—by the California stem cell program.

This post originally appeared on HuffPost.

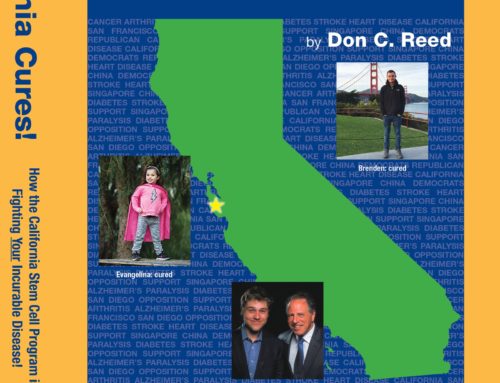

Don C. Reed is Vice President of Public Policy for Americans for Cures, and he is the author of the forthcoming book, CALIFORNIA CURES: How California is Challenging Chronic Disease: How We Are Beginning to Win—and Why We Must Do It Again! You can learn more here.