Meet Dr. Andrew McMahon. He’s the Principal Investigator at the University of Southern California’s (USC) Stem Cell McMahon Lab. Dr. McMahon’s research focuses on the generation and repair of the kidney by identifying the regulatory processes that maintain, expand and differentiate kidney stem cells to the mature cell types of the functional kidney. In the adult, they are identifying the cellular and molecular mechanisms at play in repairing damage on acute injury. These lines of research will enable complimentary strategies to treat kidney injury and disease.

We spoke to Dr. McMahon about his research and how stem cells are offering insights into kidney disease.

Q. What is one new and exciting stem cell discovery in your area of research?

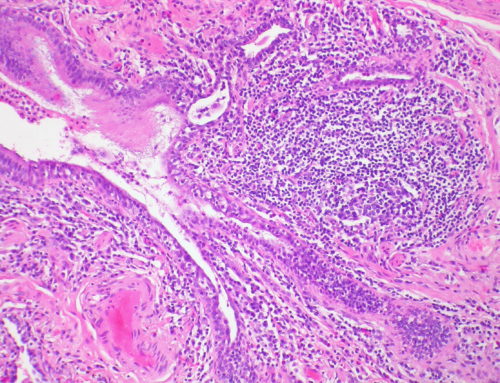

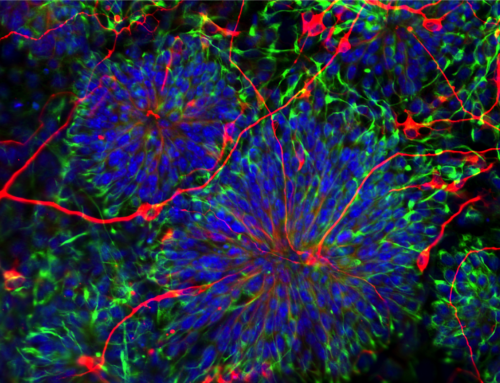

One of the most exciting discoveries has been the ability to take stem cells and generate kidney-like cells that have a structure reflecting the normal organization of the functional unit of the kidney, a nephron. For the past few years, we have been trying to use these models to understand how a normal human kidney develops, which will lead us towards the discovery of ways to regenerate it.

We are taking a systematic approach to understand the underpinnings of normal kidney development. To do this, we are using stem cells and making organoids in the lab. These are mini-units of our organ systems. We can study kidney development in this way and we can also use these organoids to model diseases. Interestingly, one of the most common inherited kidney diseases is autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Up until now, scientists were reliant on animal models for the study of this disease, but such models cannot precisely model the human condition. Now, we can make these organoids in a dish and have more directed approaches to understand the the human disease, as well as development and regenerative processes.

Eventually, as the field progresses, we’ll be able to connect different organs together. This is a critical component of stem cell research. I think there is often a lot of emphasis on the idea of putting cells into patients but we should not forget the other applications of stem cells such as disease modeling and drug screening, both of which hold enormous possibilities.

I think there is often a lot of emphasis on the idea of putting cells into patients but we should not forget the other applications of stem cells such as disease modeling and drug screening, both of which hold enormous possibilities.

Q. What is the best way for advocates to rally support for stem cell research?

We need to have more discussions about the broader use of stem cells in the public domain. We need to talk about it on the news, in the newspapers, social media, etc. I’m often quite surprised by the limited knowledge of well-educated people about the applications of stem cells. There are many things that can be done such as hosting events and having a speaker come in to talk about regenerative medicine, laying out all the different approaches – from being able to use stem cells directly, to genetically modifying cells to treat specific diseases, to using them indirectly because they generate other cell types that are useful or even more indirectly to generate a model in a dish. We need to spell out the variety of different ways in which we can utilize stem cells and help the public understand that together these strategies enable us to translate our understanding of how systems develop, are maintained and repaired to create new therapeutic approaches.

Q. You’re at a dinner party and someone asks you why you believe in the power of stem cells to treat chronic conditions. What is your response?

If someone asked me this at a dinner party, I would say: I actually see an inherent problem in the way this question is phrased: stem cells are powerful, but there are other ways to treat chronic diseases founded on developmental understanding. I would take a step back. Of course, we have to recognize that there are many good examples of how stem cells can treat chronic diseases. For instance, by putting stem cells into a patient with a blood disorder, we can reconstitute the blood system. But when it comes to chronic diseases, we’re not just trying to fix just one thing. Typically, we are dealing with a lot of other things at once. For instance, if someone had a heart attack, they’ve lost normal heart tissue. Those lost cells are then replaced with fibrotic tissue which stops leakage but has no function. What if you could change those fibroblasts back into the functioning cells of the heart known as cardiomyocytes? Reprogram those cells. There are approaches to do this that don’t involve a stem cell.

Then let’s look at my system, the kidney. There is no good evidence that stem cells play a major role in repair and regeneration and this is a paradox within our organ systems. While some organ systems have stem cells at their base active each day to replenish tissues, other systems like the muscle, liver and lungs have stem cells that operate at low levels called in when they need to be. And then in kidney, there is really no strong evidence that tubular repair is driven by stem cells. The public wants a word and stem cells conjure up images of cell transplantation and repair. But that’s a limited scope. I think it’s important to convey the bigger picture which is regenerative medicine. Stem cells are a key part of regenerative medicine but there are many important avenues where stem cells play a less direct role.